From the Perfect Farm, the Perfect Crime

In a world where much had to be built from scratch, the ability to cook, slaughter, preserve, and care was absolutely essential for survival. Women were responsible for food, cleanliness, medical care, childbirth, and household economy—in short, everything that made a home function. What had been considered homemaking knowledge back in Norway became, in the New World, a lifeline. Women’s knowledge wasn’t just everyday wisdom. It was survival knowledge.

"To keep meat for a long time, it must be well salted and stored in a cool place."

– Hanna Winsnes

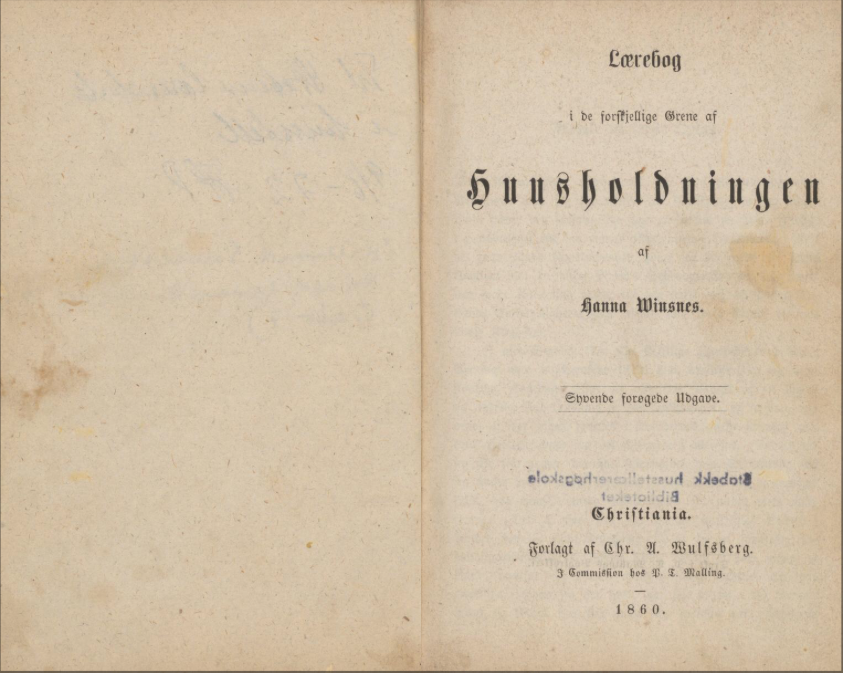

In 1845, a book was published that would stand as a monument to this role: Textbook in the Various Branches of Household Management by Hanna Winsnes. It offered women detailed guidance in everything from cooking and preserving to butchering, sewing, nursing, and brewing beer—in short, the skills needed to keep a house, home, and family going. This was not just a cookbook, but a handbook for women’s lives, order, and morality in a time when a woman’s domain was the kitchen and the household. Importantly, most Norwegians at the time still lived in rural areas, where a wife and mother was also expected to contribute to farm work. Thus, household management included not only domestic duties but also the practical knowledge required to help sustain small-scale agricultural life.

Winsnes emphasized that she hadn’t written the book out of a feeling og superiority, but because her own inexperience had shown her how vital such knowledge was:

"It was not because I believed I knew more than other housewives that I wrote this book. On the contrary—it was my own inexperience in youth, when I cared for my sick mother, that made me realize how difficult it is to lack knowledge. It awakened in me a strong desire to learn."

On the surface, the story of Belle Gunness—a Norwegian woman who emigrated to America and became one of the world’s most infamous and mythologized serial killers—seems far removed from the moral guidance of Winsnes’ cookbook. But it is precisely in the contrast between these two women that a compelling story emerges—one that sheds light on how knowledge, expectations, and gender shaped a woman’s life path in the 19th century.

What happens when the same knowledge meant to preserve life and offer care is used to manipulate, conceal, and kill?

There’s no evidence Belle Gunness ever read Winsnes’ book, but she was born in 1859—at a time when the book had already circulated for over a decade and was in its fourth edition. The first edition was published in 1845, with new printings in 1846, 1848, and 1860. This speaks to how popular and widespread the book had become. It was used in many Norwegian households, especially among those with some means and aspirations—both in bourgeoisie families and in self-sufficient farming families.

Winsnes’ book represented not just an ideal but a body of knowledge that extended beyond the printed page. It reflected a broad tradition in which much was also passed down orally or through hands-on learning from mother to daughter. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that Gunness grew up with some version of this same knowledge base: how to run a household, take responsibility, and exert power quietly.

And because Winsnes’ book was so widely distributed and reprinted within a short time, it can also be seen as a timely reflection of the kind of knowledge housewives were expected to master.

This article takes a closer look at what was considered common knowledge for women in Winsnes’ time—and what happens when that knowledge is used in entirely different, darker contexts. What does that say about the era—and about how fragile the line between order and chaos can be?

Household as Power and Control

Hanna Winsnes’s cookbook is not just about recipes and cleaning tips. It is a document that reveals how the household was organized and managed, with the woman as the highest authority in a small domestic hierarchy. For everything to run smoothly, she had to keep track of it all: who was responsible for the milk pails, how to polish the tin pots, and when it was the right time to buy provisions.

"To clean a pot that has been used for fatty things, especially during butchering, use sawdust, hot water, and coarse sand, and scrub with a birch twig."

— Hanna Winsnes

Winsnes writes that a good housewife should not delegate important tasks to servants until she is sure they can be trusted. She also advises maintaining regular inspections of kitchen tools—not as a punishment, but to instill a sense of responsibility and respect. The household is presented as a small system in which order, division of labor, and oversight are absolutely essential. This reflects a time when women had very little power in the public sphere but were expected to exercise full authority and control within the private space of the home.

"When slaughtering a pig, one should drain the blood well in advance and place it on a slanted surface so that all the blood runs out. Then it should be butchered precisely along the joints."

— Hanna Winsnes

Among her many practical tips, we find instructions on how to make soup from a calf’s head, clean house using hot sand, sew a collar on a man’s shirt, preserve rhubarb in sugar syrup, and butcher a pig the proper way. She explains how to sew straw-filled pillows, prepare a winter household budget, raise children, and care for a sick family member.

All of this knowledge made the woman the linchpin of the household—a combination of caregiver, manager, economist, and foreman.

In other words, the knowledge expected of women wasn’t just practical—it was strategic. It involved logistics, leadership, budgeting, and motivation. But this knowledge also served as a limitation—a set of expectations that bound women to the invisible labor of the home, leaving little room for deviation or personal freedom. It was knowledge that could provide security, but also define the boundaries of a life.

It is therefore not surprising that a woman like Belle Gunness, who likely grew up within these same expectations, might apply parts of this knowledge in entirely different—and far more disturbing—ways.

In Winsnes’s world, control was a virtue.

In Gunness’s world, control became a tool for manipulation and concealment.

It’s not hard to see how the same kind of knowledge can branch out in very different directions, depending on circumstances, power, and motive.

These substances could quite legally be part of a household in the 19th and early 20th centuries—and no one would necessarily have raised an eyebrow.

In a woman’s world shaped by self-sufficiency and limited access to modern medicine, such substances were part of the everyday toolkit. And in Gunness’s case, no one found it strange that she frequently purchased large quantities of kerosene and fuel—ostensibly for burning waste… or bodies. These materials were available for practical purposes, but just as easily used to erase evidence. It’s not hard to see how the same kind of knowledge could branch off in very different directions, depending on one’s circumstances, power, and intent. In Gunness’s world, control became a tool for manipulation and concealment.

A Quiet Household – and a Quiet Eradication

Looking through the lens of Hanna Winsnes’s cookbook, we see how 19th-century domestic knowledge wasn’t merely about trivial tasks—it was about control, structure, and survival. It was knowledge for life. But in the story of Brynhild Paulsdatter Størseth—better known as Belle Gunness—we encounter a distorted mirror image of this ideal of the household.

Gunness grew up in a frugal and tightly regulated home in Selbu, where every skill and resource was essential to the family’s survival. From her upbringing, she knew cooking, cleaning, budgeting, and caregiving. She emigrated at a young age to America and lived for a time with her sister and brother-in-law in Chicago, where she reportedly worked for a butcher. This period likely expanded her practical knowledge and independence before she married in 1884 and eventually established herself as a farmwife and widow in La Porte County, Indiana. The knowledge she had acquired—both in Norway and during her early years in America—gradually became a tool of power.

In Winsnes’s world, a good housewife “never delegates more important matters to a servant until she is fully convinced of their reliability.” Belle Gunness, on the other hand, chose to do everything herself: butchering, preserving, managing finances, decorating, and social staging. Outwardly, she appeared dutiful and hardworking—a grieving widow and loving mother. She served traditional dishes like trøndersodd (beef stew) to the many men she lured to her farm and used her mastery of household management to cover her tracks. The domestic arts became a disguise for murder.

Winsnes valued cooking as both an art and an economy—boiling calf heads into soup, preserving rhubarb, or planning the winter pantry. Gunness used those same skills to create a sense of safety and anticipation in those who visited—before poisoning them and vanishing with their valuables. She knew how to slaughter, how to store—and how to hide.

Winsnes emphasized precise bookkeeping and yearly tracking of consumption. Gunness was a master of insurance fraud, will manipulation, and cash flows too complex to trace. Where Winsnes kept a ledger of household expenses, Gunness kept a notebook of new victims’ names.

Cleaning was at the heart of Winsnes’s system: things had to be in order, properly washed, performed with the right tools and techniques. Gunness applied the same discipline— but to remove evidence. Lime, soil, routine. She had full control. Nothing was accidental.

Historical sources tell us she moved money, hid bodies, and knew when to shift from a warm demeanor to cold calculation. She used household knowledge as both a psychological and physical mechanism of control. Everything was kept in perfect order—until her farmhouse burned down in 1908 and the revelations began.

Winsnes recommended setting aside one day each week to inspect the household. Gunness did the same—but to ensure that no bodies were surfacing from the soil.

It is in this parallel that we see how thin the line is between the nurturing home and a controlled space for systematic extermination. The skills and knowledge a woman must master, as Winsnes understood it, could be empowering. For Gunness, this became a tool of terror. And perhaps that’s precisely why we must not trivialize the history of the household.

The stories of Winsnes and Gunness are not just women’s stories. They are stories of how knowledge shapes lives. They challenge us to look at what seems small—food, order, care—with new eyes. Because within the quiet household lies a quiet force.

Hanna Winsnes (1789–1872) was a pioneer in both domestic science and literature. Today, she is best known for her groundbreaking 1845 cookbook Lærebog i de forskjellige Grene af Huusholdningen, which combines recipes with practical advice on everything from butchering and hygiene to household budgeting and child-rearing. The book played a central role in professionalizing the role of the housewife and went through numerous editions. Winsnes was also Norway’s first female novelist, publishing under the pseudonym Hugo Schwartz. In all her writing, she emphasized the importance of order, knowledge, and divine providence in everyday life.

Belle Gunness (born Brynhild Paulsdatter Størseth in 1859, Selbu, Norway) grew up in poverty and entered the workforce as a child. She emigrated to the U.S. in 1881 and settled in Indiana, where she became a farm owner and widow. Over time, she was linked to numerous suspicious deaths—often of men she had lured through personal ads offering marriage. Considered one of the most notorious serial killers in American history, her farm burned down in 1908, revealing dozens of human remains. Belle was never definitively identified among the dead, and her fate remains one of the great unsolved mysteries. Her life continues to intrigue journalists, historians, and true crime audiences alike.

Sources:

Hareide, J. (2009). Hanna Winsnes. I Norsk biografisk leksikon.

Melien, H. (1978). Belle Gunness: massemordersken fra Selbu. Oslo: Grøndahl.

Shepherd, S. E. (2005). Gåten Belle Gunness: Seriemordersken fra Selbu (S. B. Løken, Overs.). [Oslo]: Schibsted. (Opprinnelig utgitt som The Mistress of Murder Hill)

Store norske leksikon. (u.å.). Belle Gunness.

TV 2. (2020, April 25). Brynhild (49) lokket med sex og trøndersodd – 40 menn ble grisemat. TV 2.

Winsnes, H. (1860). Lærebog i de forskjellige Grene af Huusholdningen [Lærebog i de forskjellige grene af husholdningen]. Christiania: Wulfsberg.

get updates on email

*We’ll never share your details.

Join Our Newsletter

Get a weekly selection of curated articles from our editorial team.

.svg)