Lonely Widow Seeks Help on Her Farm

Easter Crime from the Darkest Corner of the Emigrant Story – Based on a True Story

Lonely Widow Seeks Help on Her Farm

Every year at Easter, something quite special happens in Norway: we don’t just go skiing – we read crime stories. This tradition, known as påskekrim (Easter crime), has been around for over a hundred years, filling bookshelves, TV screens, and podcasts with mysteries, murders, and dark tales throughout the holiday.

It all began in 1923, when the novel The Bergen Train Robbed Last Night was launched with a dramatic front-page ad in Aftenposten – so realistic that readers thought it had actually happened. Since then, crime fiction has become a beloved Norwegian Easter tradition.

This Easter, we’re sharing a story that stands apart from the others we tell in Vågespel. Among the many brave women who emigrated from Norway to America in the 19th century, there are also lives that don’t fit into any ordinary category.

This is an Easter tale – written from the life of a real woman and true events. She is an exception, but she casts a long shadow over what a “new life” across the ocean could also bring.

Happy Easter – and welcome into the darkness!

The Little Cow

She was born on a frosty November night, in a house with no floor. No one sang. Her mother clenched her teeth and pushed out yet another child, eyes fixed on the black ceiling. She was number eight. Brynhild. A name that hung in the air like the acrid smell of smoke. A sound that wouldn’t be spoken aloud too many times—because it didn’t need to be. Brynhild would learn to be quiet. Like the snow.

There was only one cow. Her name was Grålin, and she was dumber than most cows. She had big eyes and often stood staring at the mountain as if she were waiting for something. Grålin gave little milk. She had no more calves. But she stood there. In the barn. Every day. And Brynhild went there every morning, while the other children ran of to school.

–You take care of the cow. That’s all we’ve got, her father said.

And Brynhild did. She never spoke to Grålin, but she sang. Softly, so no one could hear. A kind of quiet, monotone melody that filled the air like milk-fog. Grålin liked it. She stood perfectly still. Almost as if she were listening. It was just the two of them.

When she was nine, the schoolteacher brought a message: Brynhild had to sit all the way in the back. Where it was cold. They didn’t have enough chairs. Or maybe it was because she was so big. Her body grew like a birch tree. Long arms that hung over the desk. Long legs squeezed under the tiny bench. And she sat there, eyes fixed on the backs of the others’ necks, without blinking.

Once, one Sunday in February, she was allowed to go to church. She’d polished her shoes with juniper. Her dress was too short. But she went. And when they arrived, she had to sit in the back there too. The child of mercy. That’s what the pastor called her later, thinking she hadn’t heard him. Child of mercy. She wasn’t sure what it meant, but it sounded like something she didn’t want to be.

She was twelve when Grålin collapsed. Right there in the barn. No sound. Just a heavy, dull thud. Her father came running and saw what had happened.

–Well. I guess we’ll eat her, he said, and patted Brynhild on the shoulder.

But she didn’t answer. She just sat there in the straw, dirt on her dress and something cold behind her eyelids. A calm. It was something she knew then, but couldn’t put into words. She would not stay here. And she would not forget the sound of a body that no longer wants to be in the world.

No one sang when they slaughtered Grålin. But Brynhild did. Inside. A deep tone that vibrated up into the smoke in the chimney. That was when she began to understand what she was made of.

The Barn Dance

They said it was him. The son of the richest farmer in the village. The one who had new leather gloves from Trondheim and rode like a nobleman down the village road while the others walked in their worn-out shoes to market. Brynhild didn’t see him often, but she always knew where he was. The sound of his footsteps in the gravel. His laughter. The smell of tobacco and snow.

She was sixteen that summer. Her skin had the warm brown hue of soil. It was hot, and she had been allowed to go to a dance for the very first time. In the barn. It smelled of sweat and burnt juniper, and a mother with a red ribbon in her hair sat watching everything.

He didn’t dance at first. Just sat in the shadows, arms crossed. But after a while, he came over—quietly, as if by chance. And she danced. Brynhild didn’t know what she was doing. She just floated. And he held her tightly around the waist. He laughed softly and said something she wouldn’t remember later. And out in the dark, between hay poles and the sharp scent of earth, they got far too close. He didn’t promise her anything, but she believed he didn’t have to. Because he had seen her.

No one wrote down what happened that night. Only that she stopped eating. That she held her shoulders higher than before. And that her singing changed—quiet and tense, like a fiddle string out of tune.

And then one day: the kick.

No one knows exactly what happened. Whether he knew. Whether it was an accident. Only that she lay there for four days with her hands over her belly. Her mother placed cold water on her forehead. Her father said nothing. And after that, it was as if something broke inside her. She was no longer the girl who tended the cows. She didn’t answer when people spoke to her. She picked up firewood as if she wanted to snap it in two.

When the farmer’s son died a few weeks later, they said it was stomach cancer. But the village knew. No one said it out loud, but everyone knew. Because he’d gone around complaining about stomach pain just days after the dance. And his eyes looked different. As if he knew something had struck him.

No one asked questions. What could they do? He was buried with music. She sat at the back of the church. Same place as always. But this time, she sat with her back straight, and she sang along. And no one saw the smile—small, faint—on her lips.

That was the autumn she began saving money. With her hands. With her back. With everything she had. Because she knew that one day, she would leave. And never look back.

Across the Ocean

There was a dark cubbyhole beneath the stairs where she had hidden the money. A small leather pouch tied with rope. Exactly fifty dollars, and the stinking coins were stained with the sweat of her palms after three years working as a dairymaid in Stjørdal. Three winters of cracked hands and scabbed skin. No love, only labor. But the money was real, and she held it in her hand for a long time before tying the pouch tight and fastening it beneath her dress with a leather strap.

She didn’t say goodbye. Just left. A train, a boat, and then another boat. She knew where she was going. Her sister Nellie had written about the factories and the straight streets. About the smell of burnt sugar in the air and women who had their own money. Chicago.

Crossing the ocean, she sat completely still. Men asked her name. She didn’t answer. She didn’t sing. She just sat, a scarf over her head, her eyes fixed on an invisible line far away.

One evening, an older man sat down beside her. Said he was from Kristiansand and worked as a carpenter. He offered her a slice of bread with pork fat. She didn’t take it. But she looked at his hands. Long, rough fingers. Something inside her stirred, like a school of cold fish. She stood up and walked away.

She didn’t drink coffee, only water. Didn’t speak to the other women. But she stayed up late, writing in a small, hardcover notebook. Observations. Who had gold rings. Who lied. Who stared too long. Her gaze cut through people like a knife through butter.

When they saw land, people began to cry. Some sang. She did neither. She stood at the very front. She had cut her hair short. Dyed it with a mix of ash and wood shavings.

Brynhild was gone.

She was Belle now.

She stepped ashore, her legs stiff, and said her name out loud for the first time:

— Belle. Belle Sørensen.

No one asked anything else.

Chicago Blues

His name was Mads. A quiet man with watery eyes and a cough that never let up. He worked in the packing house by the river and called her his Nordic angel. There wasn’t much angel in Belle, but she smiled when he said it. They walked arm in arm along docks full of rats and steam, and he asked if she’d marry him. She said yes—but only if the store would be hers.

The clothing shop opened on a Tuesday. With lace curtains and a tablecloth she had crocheted herself. The customers never came. But the fire did. One night, it all went up in flames. Belle stood outside barefoot, children in her arms, with a calm expression on her face. As if she knew this was only the first step. Mads stood beside her, coughing in the smoke.

They got money. A good sum. And more followed. Children came. Four of them, maybe three. Not everyone knew which children were actually theirs. Jenny Olsen, the daughter of a Norwegian sailor, lived there too. A quiet girl with steady eyes. She disappeared later, but no one quite remembers when.

Caroline died first. Then Axel. Both with the same symptoms: nausea, fever, convulsions. The doctors said colic. Belle said nothing. Just clenched the last insurance payout in her hand and tore up the strawberry plants in silent fury.

Mads died on a Tuesday. The day both of his life insurance policies overlapped. He’d been playing with the kids in the yard, the neighbors said, and just a few hours later, he lay cold in bed. The doctor found traces of arsenic but concluded it was heart failure. Belle wiped away a tear and carried her grief with strange dignity. She received $8,500.

Oscar, Mads’s brother, wanted to exhume the body. But he couldn’t afford it. An autopsy cost more than he owned. Belle packed up and left. Found herself a new place. A fresh start.

She bought land. 40 acres. With money in her pockets and blood under her fingernails. That’s when she brought out the belt.

A thick leather belt. And a knife.

That’s when Gunness Farm was born.

Invisible Holes

It started with a smell. Sweet, metallic—like raw meat in the sun. One neighbor said it was the pigs. Another figured it was just a trash heap that should’ve been cleared out long ago. Belle herself said nothing. She served coffee with sugar, trøndersodd (beef stew), and fresh sausages that made men close their eyes and sigh like children. There was always someone eating—and always someone disappearing.

She was a giant. A woman nearly six feet tall, with arms like a blacksmith and hips that had carried four children—or five, if the rumors were true. She carried the pigs herself. Butchered them herself. No one knew what she did with the waste. But she had a way of digging. Fast. Precise. Almost soundless.

Ray Lamphere was the first to see. He came to the farm one afternoon, hungover and unsteady on his feet, boots heavy with soil. She hired him to chop wood and dig ditches. But he saw more than he was supposed to. She called him a weakling but let him stay in the woodshed—as long as he kept his mouth shut. Ray had eyes that disappeared under heavy eye lids and a smile that always came too late. He loved Belle. That was the one thing he never said out loud.

Men came from all over the Midwest. They came by train, with suitcases, money tucked inside their jackets, and hope in their hearts. Her letters were full of promises. “Wealthy widow seeks well-off gentleman for possible marriage.” And when they arrived, she gave them cake. A room. A glance. And then—silence.

Ray saw them. One. Then another. He saw how she tilted her head and laughed so softly they forgot to be afraid. He saw how she led them into the house—and how, hours later, she came out alone. Hands in her apron. A tightness in her neck, like she was carrying a thought she wasn’t willing to share.

And he dug. God help him, he dug.

– What’s this hole for? he asked once.

– Garbage,” she answered. In the same voice she used when singing lullabies.

Afterward, he stood for a long time, staring at his hands. Dirt under his nails. Blood in his bones. One day he would tell someone. But not yet.

Because one evening, she sat at the kitchen table reading a new letter. Her eyes smiled. Her lips moved silently. She tucked the letter into her pocket, stood up, and said:

– A new one’s coming soon. From Hallingdal. His name is Andrew.

Ray said nothing. He just stared down at the table. And the room around them went quiet.

That was when he understood: There were no more trash heaps. Only invisible holes—

and a woman who never looked back.

“Bring All Your Money”

There was something about her letter. It wasn’t just the words. It was the rhythm—this strange, almost erotic music between the lines. “I am lonely, and my farm needs a man like you.” And: “Please sell everything you own, break off all contact with your family, and bring all your money with you.”

She wrote with a steady hand, flourished loops and careful curves, folding the page with care. She scented it lightly with juniper oil. And she knew exactly what to say. The men didn’t need anything more. A few letters, and they were on their way.

Into her claws.

Into the earth.

George Anderson came first. He had a pocket watch with engraved initials and a soft cough from a childhood spent at the sawmill. He sat at the kitchen table, eating sodd, saying her sausages tasted like a dream of Norway. Belle smiled, refilled his coffee cup, and said nothing more.

But George woke up. He woke in the middle of the night—and there she stood, a woman with a candle in her hand, staring down at him. She said nothing. Just stood there. Watching. The flame flickered in her eyes. And something in her face looked like a mirror image of death.

He shot out of bed, put his pants on backwards, and ran—barefoot through mud and darkness. He didn’t stop until he smelled cows and heard trains in the distance. He told his story later, but no one quite believed him.

Because who runs away from the love of a beautiful widow with her own farmland?

Andrew Helgelien came soon after. A Hallingdal man with a strong back and money sewn into the lining of his coat. He’d written to Belle for over two years. She had sent him photos of herself—soft lighting, a sly smile. He thought he knew everything about her. But she knew more about him.

They went to the bank together. She held his arm, like a true sweetheart. He withdrew the money. She smiled. A few days later, he was gone. Belle said he’d moved on. People nodded. After all, plenty of folks were moving on.

Ray Lamphere knew better. He saw Belle’s shadow at night. Heard the knife on the whetstone. Heard the sound of something heavy being dragged across the floor. And he knew: Andrew was no longer a man. He was a hole. A name in the dirt. Another chapter in her book.

And she sat there. With a new letter. A new pen. A new melody in her sentences. She wrote like a composer. And every note brought another man to her door.

With his money.

And his head bowed.

The Meat Grinder and the Child

It was a soft rain the day Peter Gunness arrived at the farm. He had a five-year-old daughter and an infant in his arms. His wife had died, and he saw Belle as a lifeline. She greeted him with a nod, not a smile. But he was allowed to stay. And they married—quickly. It was supposed to be safe, she said. For the children.

Little Jenni died seven days after the wedding. Belle said it was colic. She told the doctor the same, and he nodded, though his eyes wandered. Peter put his hands to his head but said nothing. Who could understand grief better than Belle, he thought.

He didn’t know she had plans for more than grief.

Eight months later, he lay on the kitchen floor with his skull split open and his nose crushed. Belle explained it like this: a meat grinder had fallen from the top shelf and struck him on the head. It was an accident, she said. And she said it with such weight, with such a tender voice, that they believed her. Again.

His brother, Gust Gunness, did not. He arrived in polished black shoes, asking pointed questions. Who had seen the grinder fall? Why hadn’t Peter said anything? And why wasn’t Swanhild, Peter’s daughter, allowed to stay with Belle?

There was an argument. Gust wanted Peter’s insurance money. Belle wanted Swanhild. She got neither. Gust took the girl and disappeared. A few months later, Belle gave birth to a boy—Phillip.

No one knew she was pregnant. No doctor had seen her. No midwife had been there.

– Back in the old country, we didn’t take to our beds after childbirth, Belle said when a neighbor found her the next day, knee-deep in the laundry.

The judge ruled the child was Peter’s, and so Belle received money again. Money—and a new child. Phillip was quiet. He didn’t cry much. He just watched. With wide eyes and hands that reached for her belt.

And while the neighborhood started asking questions, while the whispers crept through the church aisles, Belle began to plan something new. In solitude. Knife sharpened. Eyes fixed on the windows.

More letters came. More men followed.

But first, she had to deal with Ray Lamphere. Because he had seen too much. And the most dangerous kind of man is bitter—and alone.

She saw him one evening, standing by the woodshed. He just stood there, staring at her house as if he could see through the walls.

– He’s going to kill me, she told the police. – Or burn down my farm.

But she knew better.

It wasn’t Ray she was afraid of.

It was reality.

And reality had started knocking on the door.

Smoke

Ray Lamphere had started walking around the house at night. Belle said he looked through the windows. And that he sniffed around like a starving wolf. She went to the sheriff and said she was afraid. She wanted him declared insane. They sent him in for evaluation. Three doctors examined him. All said the same: he was sane. Just broken.

Ray didn’t say much. But he watched. And he knew what was buried in the ground. He knew where they were—the ones who never got to send their final letter home. He knew what she did after the coffee was poured. How she walked out to the shed with kerosene and a shovel. And he knew how she sang while she dug.

Belle knew too. She knew Ray would start talking soon. She knew the police had started asking questions. That Gust Gunness wanted his brother’s death investigated again. That something was coming. A kind of movement in the air. A gust of wind at her back that didn’t come from outside.

So she began to plan.

First, the will. She had a notary draft it carefully. She left everything to the children. In case anything should happen.

Then, the kerosene. Five gallons. Bought in two rounds, from two different places. Small jugs she poured into a barrel in the barn. Joe Maxson, the new farmhand, didn’t ask questions. He later said he thought she was preserving meat.

On April 27, she sat at the table for a long time. Wrote three letters. One to her lawyer. One to a friend. And one to a female relative in Chicago. In the letter, she said she was being threatened. That Ray was going to kill her. That she was afraid. She enclosed money for a gravestone.

The night came without a moon. The farmhand was asleep in his quarters. He woke to a click. Then a smell. Sweet and burning, like tallow and bone. He jumped up. The door was hot. He kicked it open and ran.

The fire devoured the house in less than half an hour.

The firefighters came, but it was too late. The house lay in ruins, glowing red. In the basement, they found three children’s bodies—Phillip, Myrtle, and Lucy. Laid side by side. At the far end, there was a fourth body. Small. A woman. Headless.

The body was delicate. Around five-foot-five. Belle had been a giant, the neighbors said. This one was too small. Too light. And where was the head?

A dentist later claimed he recognized the dental bridge found in the ashes. Said it was Belle’s. The judge accepted it. And the local newspaper printed: “An Honorable Woman Dies in Flames.”

But Maxson shook his head. And Ray laughed in his jail cell. Laughed long—

Until he coughed blood into his hand and stared at the wall like he was seeing something no one else could see.

She wasn’t dead. Not Belle.

She was the wind that shifted.

She was the light from a match—just before it burns down to the fingers.

The Graves

Andrew Helgelien’s brother drove in from Dakota. A Hallingdal man with a jaw like a plow and eyes that never let go. His name was Asle. And he didn’t believe a word the sheriff said.

–My brother would never have left without writing, he said. –And not without his money.

He demanded digging. Sheriff Smutzer hesitated, but Asle stood there with his arms crossed, feet planted in the earth, and said he’d start digging himself if he had to use his bare hands. So they began. First by the chicken coop. Then along the picket fence. And finally—by the pigpen.

There was a sack. Then another. And another. Burlap bags, soaked with dirt and rusted metal. In one of them was a body without a head, dressed in remnants of Norwegian homespun. A pocket watch. The initials A.H. engraved inside.

– Andrew, Asle whispered. Almost like a prayer.

Then they found more. Men. Women. Children. A fetus. Some without heads. Others without legs. Dismembered with precision. Stored like food. Belle had dug with a calmness that only exists in those who believe they’re doing what’s right.

Joe Maxson said he had been told more than once to fill in holes with dirt. She told him it was garbage. He believed her. Because she sang while she pointed.

The last body they found before the sheriff stopped the digging was Jenny Olsen. The daughter Belle claimed had been sent to Los Angeles to study law. Jenny was buried in the same dirt as the men. A scarf tied around her neck. She was only a child.

Reporters came. Photographers. Doctors. Rumors.

Over forty bodies, some said. No one knew for sure.

Because the sheriff ordered the graves covered with a tarp.

And the rumors were kept alive—fed by their own rotting root.

Ray Lamphere sat in jail. And now, he talked.

He told everything. About the coffee. About the poison. About the hammer. About how Belle cut up the bodies, and how he carried them out. About how quiet it could be when a body falls. And how heavy the earth is when it doesn’t want to let go.

He said, –I helped her. But I didn’t know it was wrong.

She sang, you know. She sang while she did it.

One year later, Ray died of tuberculosis. But before he went, he said one last thing:

–She’s not dead. She had a plan. And I helped her find another woman. A body that could take her place.

No one ever found the head of the slight woman in the basement.

But someone claimed they saw Belle. Later. In Los Angeles.

Not as Belle. But as Esther Carlson.

And after that, no one knew anymore—

what was buried,

and what was still alive.

The Woman Who Doesn’t Die

She sat behind a window in Los Angeles, stirring her tea with a silver spoon. She called herself Esther now. Esther Carlson. Widow, she said. Recently engaged to a wealthy businessman who died far too suddenly. The police suspected arsenic. But she said he’d been weak. He had a sorrowful look, she said, as if he knew life wouldn’t keep him long.

She didn’t look like Belle Gunness. Smaller. Softer, said those who knew her.

But then there was one thing: the photos.

When she died—of tuberculosis—they found a box in her closet. Inside were several photographs. Of children. Of the children. Children many believed were the same ones Belle had once claimed as her own. And a letter, never sent, with only one sentence:

“I don’t want them to know.”

No one could prove anything. Belle was dead, the court said. Esther was someone else.

But something lived on.

The story.

The eyes.

The voice that sang while she dug.

And the headless woman—the one who never got a name—was never identified.

Asle Helgelien returned to Dakota. With his brother’s watch in his pocket and soil in his soul. He never spoke of her again. But every Saturday, he stood in his yard and stared toward the horizon. And when someone asked, he would only say:

–She’s not gone. She just changed her skin.

Years passed. Belle’s farm grew wild. The pigpen turned into raspberry thickets. Children played there, unaware. But on certain nights, you could hear something. A stirring in the grass.

A song.

Low.

Dark.

Like a string that was never tuned.

And one day, many years later, a Norwegian-American pastor received an envelope.

No return address. Inside was only a photograph. A woman—older now—with dark eyes and a small scar on her forehead. On the back, it said:

“I remember Grålin.”

No one understood what it meant.

But she did.

Because some women don’t let themselves burn.

They simply change their shadow.

The Last Meal

In a cell with thick stone walls and a door that never opened quickly, Ray Lamphere lay trembling. Tuberculosis had eaten through his lungs, but not through his memories. The memories were intact—sharp and gleaming inside him, like freshly honed knives.

He had eaten his last meal—salted pork and sourdough bread. He spread the butter with a crooked knife and laughed to himself. –She would’ve done it better, he told the guard. –She knew how to make food that made men forget everything.

A priest came. Ray didn’t want to talk to him. But he asked for paper. He wanted to write it down. For the record, he said. Or for revenge. Or maybe just for peace. No one knew.

On four sheets, he wrote everything: About the hammer. About how Belle always looked at them before she struck. As if she were waiting for a sign from something greater. About how she would sit at the table afterward, coffee cup in hand, palms flat on the oilcloth, and sing.

She sang while he carried the bodies. He wrote: “She thought it was art.”

He said she didn’t hate men. She despised them. They thought they owned her when they arrived. But it was she who owned them—from the first letter to the final breath. They came for love, and found a grave.

Ray wrote: “I carried thirty-eight bodies. Maybe more. I didn’t always know their names. But I knew their weight.”

He died the next morning.

A quiet sound.

No singing.

No one came.

The guard folded the four pages and placed them in a file labeled “Lamphere, Ray.”

The file was forgotten. Later found. But never used. It was too much. Too raw. Too close.

In an attic in La Porte, in a box between old sheet music and a rusted scythe, there lay a cookbook with specks of dried blood. In the margin, a note in uneven handwriting: “Too much salt, but good with pork.”

And in a dream, in another town, an old woman sat at a kitchen table,

quietly humming to herself as she sliced sausage into perfect rounds.

No one knew her name.

But she knew

what came after the meal.

The One Who Waits

Summer in La Porte arrives quietly, as if the wind doesn’t dare disturb what still lies buried beneath the ground. Raspberries grow over Jenny’s grave. A boy finds a piece of a dental plate while playing war with a stick rifle. And an old man—Joe Maxson, hands now trembling—sits on a bench and stares at the spot where the house once stood.

– It was never an ordinary house, he says. But no one asks him what he means.

In Los Angeles, women die every day. One of them dies without a name. Her body is cremated. Her paperwork missing.A medical examiner notices a mark behind her ear that doesn’t match her listed identity. But he lets it go. What’s he supposed to write?

A journalist in Chicago writes a book. He calls it The Enigma of Belle. It sells poorly. Because no one really wants to believe it. That a woman could do all of this. They say: she must have had help. She must have been insane. She must have been something other than human.

But children remember. Children remember looks, and tones, and stories that never quite let go. And one day—in 1931—a girl finds a photograph in a wallet from an estate sale. In the photo: a broad woman with a knife at her belt, two children at her side, and a smile that doesn’t reach her eyes.

The girl asks her grandmother who it is. She gets no answer. But the grandmother walks quietly into the kitchen and lets the water run, for a long time.

Some say she lived. That she simply moved on, changed her name, changed her hair. Some say she died, and that her story disappeared in the ashes. Both could be true.

But those who saw her, and never forgot, know this:

She looked at you a certain way. As if she already knew you. As if she knew your weight.

And maybe that is what will remain, when all else is forgotten:

That there was once a woman who could stir up love with a pot of stew— and bury the whole world in a shallow grave.

That she waited.

And that maybe—

she’s still waiting.

Belle Gunness (1859–1930?)

Belle Gunness, born Brynhild Paulsdatter in Selbu, Norway, in 1859, emigrated to the United States in 1881. Her life was marked by fires, suspicious deaths, and large insurance payouts—leading to her infamy as one of the most notorious serial killers in American history.

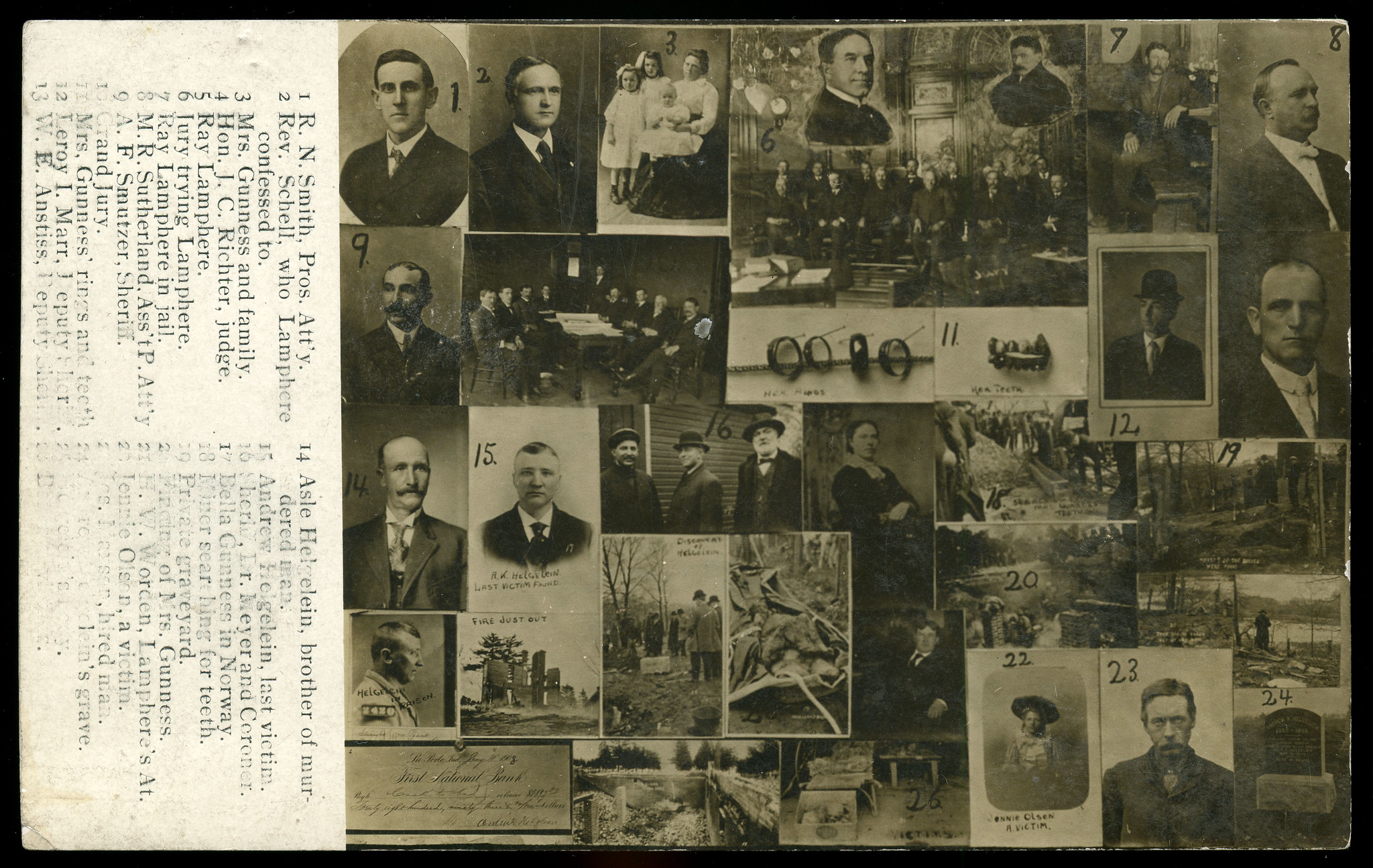

After several husbands, children, and suitors died under mysterious circumstances, police began digging on her Indiana farm. They uncovered the remains of over 40 people. In 1908, her house burned to the ground. In the ruins, three children and a headless woman were found—believed by many to be Belle. But the skull was missing, and the evidence was unclear.

She was never definitively found. Whether she died in the fire, or escaped with the money and a new identity, remains a mystery.

Sources:

Hawthorne, E. (2024). Whispers from the murder farm: The case of Belle Gunness: Inside the mind of America’s darkest femme fatale (Shadows of the Past Book 3) [Kindle-utgåve]. Cordova Consulting.

Shepherd, S. E. (2005). Gåten Belle Gunness: Seriemordersken fra Selbu (S. B. Løken, Overs.). Schibsted. (Opprinnelig utgitt som The Mistress of Murder Hill)

Haarstad, K., & Vestby, A. B. (2025, 25. mars). Belle Gunness. Store norske leksikon. Henta 15. april 2025

TV 2. (2020, 26. april). Brynhild (49) lokket med sex og trøndersodd – 40 menn ble grisemat.

Cover image: Belle Gunness and Children, 1908. Remark: From left to right are Lucy, Myrtle, Phillip, and Belle.(From a Late Photograph) Laporte, Indiana. Source Type: Postcard. Publisher, Printer, Photographer: J. H. King. Collection: Steven R. Shook. Source Flickr

get updates on email

*We’ll never share your details.

Join Our Newsletter

Get a weekly selection of curated articles from our editorial team.

.svg)